What is the Post-Cinematic?

My sense of the “post-cinematic” comes first of all from media theory. Cinema is generally regarded as the dominant medium, or aesthetic form, of the twentieth century. It evidently no longer has this position in the twenty-first . . . what is the role or position of cinema when it is no longer . . . a “cultural dominant,” when it has been “surpassed” by digital and computer-based media?

Steve Shaviro, "What is the post-cinematic?"

The concept of post-cinema points to the ways we increasingly experience and make media in multiple, dispersed, digital and networked forms (and how, in turn, this affects and “makes” our subjectivities). Not only do you likely not watch most of your media in the form of cinema or at a movie theater, you watch media on various digital devices. You don’t just watch—to take a singular example—The Walking Dead, you also watch the television show about The Walking Dead. Moreover, you don’t just watch the show and the show about the show, you read the comic book that the show is based on. You, also, don’t just read the comic book, you read blogs and social media posts about the show or about the comic, etc. Moreover, you play any number of video games based on The Walking Dead. And, also, read blog posts or watch videos about the video game. This is just one of many examples that illustrate how the media regime of the early 21st century is dramatically different from other eras.

Trailer for Richard Kelly's Southland Tales (2006).

In his book Post-cinematic Affect (2010), Steve Shaviro cites various examples of what he calls the post-cinematic media regime, from Grace Jones’ music video, “Corporate Cannibal” (2008) to Neveldine and Taylor’s film Gamer (2009). But perhaps the best example can be found in his reading of Richard Kelly’s often derided 2006 film Southland Tales. A film that stars one of our greatest living actors™ (this is a joke), Justin Timberlake. As Shaviro writes: “The film bathes us in an incessant flow of images and sounds; it foregrounds the multimedia feed that we take so much for granted, and ponders what it feels like to live our lives within it (67).” Shaviro, ultimately, argues that the film got something right about the world we live in, today, without our quite noticing it, at the time.

Screen Life

We live in a world bounded by screens. And these screens are affecting our subjectivity in very different ways, certainly from how we were affected by the cinema screen, as your Play-as-Research assignments really taught all of you. Playing a video game is not the same experience as watching a film or streaming show. One thing to think about as you go through Shaviro’s reading in the “Introduction,” which I will do with all of you in a “close reading” video, is to think about your Play-as-Research assignment as something more complicated than what Shaviro does in his writing about cinema.

I think it’s maybe useful to all of us to think about some of the defining aspects of the post-cinematic:

1. Post-cinema highlights the active role of the audience, who are no longer mere spectators but participants in relation to the screen. We can see this in examples like fandom and video games.

2. Post-cinema is based on a proliferation of different media forms, such as film, television, the internet, TikTok, viral videos, and video games. This convergence of mediated forms leads to a blurring of boundaries and the creation of new forms of media, like web series, viral videos (like “Shoes”) or video games with cinematic elements. (Which are obviously different from the earlier forms of video games.)

3. Post-cinematic forms of media often embrace nontraditional narrative structures, such as fragmented storytelling and multiple perspectives, multiple screens, immersive visual experiences (like 3D), pointing to the ways the formal elements of post-cinematic media forms disrupt linear time and space.

These are just some of the formal elements, the formal structure, of post-cinematic media forms.

Every Video is Now (Potentially) Viral

Viral is . . . I don’t know. I guess there’s a recipe for it, but I couldn’t tell you what it is.

Liam Kyle Sullivan, "Ten Years of 'Shoes”"

"Fuck you!" Frame grab from "Shoes" by the author.

Video: Liam Kyle Sullivan, "Shoes" (2006)

In 2019, I was teaching the concept of post-cinema in another course and for some reason, the viral video for “Shoes,” which broke out in 2006, the same year that Southland Tales was released, just popped into my head. I remembered reading an interview with Liam Kyle Sullivan (referenced above) several years ago and it struck me as interesting that he had no idea how to make a viral video, much less how to replicate the success of “Shoes.” Also, I think that “Shoes” is just a really sweet example of what a post-cinematic world feels like. Totally justified teenage (minor subjective) rebellion that revels in “getting what it wants,” which, of course, happens to involve shopping incessantly for shoes, and then screaming “fuck you,” over and over after numerous men have told you they think you have “too many shoes,” and “this style runs small, I don’t think you’re going to fit.”

What does “Shoes” have to teach us about media in a post-cinematic world. Why do (or did) we like “Shoes?” What can “Shoes” teach us about what makes a viral video “happen” ?And what about post-cinema?

The Screens of Global Warming

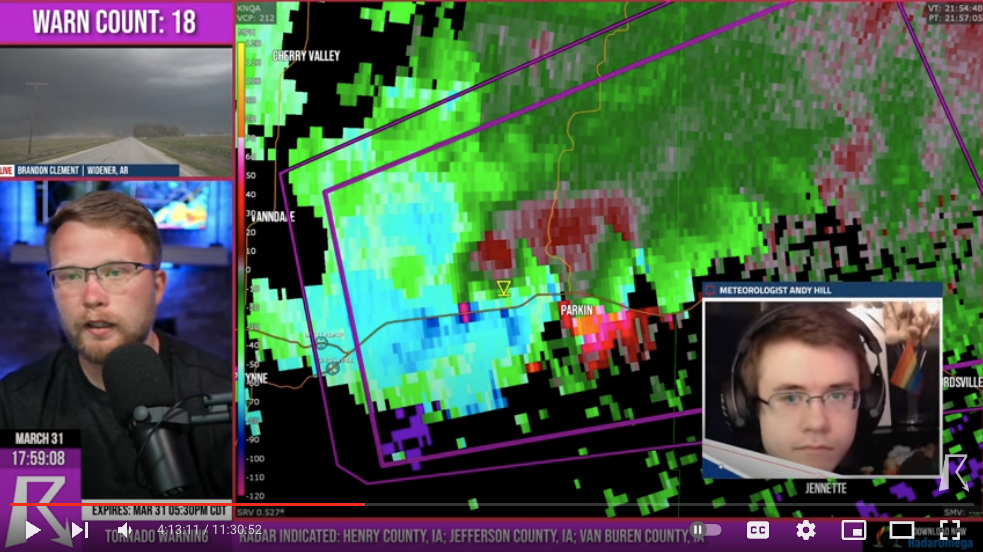

Frame grab from Ryan Hall Y'all's storm coverage of 3/31/2023 by the author.

I watched the tornados sweep across the U.S. last week (on 3/31/2023) via Ryan Hall Y’all’s live coverage of the multiple events (something like 50 tornados in one day?!), on YouTube. Ryan Hall and his team cover these weather events, which will only increase as we go further into global warming, in order to help keep people safe. It’s difficult, maybe, for us to accept that a weather report is now something interactive and looks an awful lot like Southland Tales. And, again, it may be more complex than the ways we have of thinking about forms like cinema.

In addition to the live chat, Hall’s broadcasts contain multiple meteorologists (including Andy Hill, who often has a little pride flag behind him in his shots), video and coordination with multiple storm chasers on the ground. It’s definitely a different experience to watch these events live, as the storms are happening, than afterwards, as the video below shows. Everyone is very earnest and takes it very seriously. They want to keep people safe. They know people are afraid. (“Don’t be scared, be prepared.”) Hall and his team does all of this on their own. My guess is we will see more of this as we go further into these disruptive weather events.

YouTube recording of Ryan Hall Y'all's (and team) storm coverage of 3/31/2023 (cover photo shows Andy!)

Concluding Thoughts

These are all just some examples and ideas, some elements or ways of thinking about the post-cinematic; things to keep in mind as we go through our material this and next week. I will add some additional, optional, resources on Southland Tales to our module in Canvas (and ways to think more literally about its narrative form), and I hope to make not one but two instructional videos for y’all, as soon as I am able. Take care everyone and I will see you all online. I hope this interactive blog post is a fun and different way for me to share my work with all of you, since I am too sick today to make any videos. I will also do my best to add some additional interactive elements as I am able to. As always, thank you all for putting up with me, ha ha. I really wanted to include Ryan Hall Y’all and his team in my lecture. I had been thinking about it long before this recent series of storms. I’m always trying to think about new and interesting ways to think with y’all about these big ideas we are learning about in this class. And I don’t mind saying this: these are just ideas. Either they have resonance with you or they don’t. It’s really up to you to decide if what I’ve shared with you is useful to you. More than anything, I do hope these examples I use and the things I teach are fun and different and give you new tools. Take care.